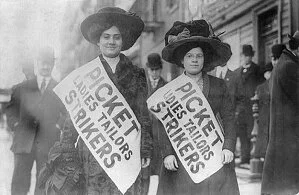

sEAMSTRESSES IN nyc 1910

Library of Congress

The Women and Their Sewing Machines

The Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire of March 25, 1911 brought the story of the deadly working conditions, starvation wages and child labor into the consciousness of the American public. Immigrant families, child laborers, union organizers and settlement workers knew the story well. The public was shocked by the deaths of 146 immigrant workers, 143 of whom were women, some as young as 14 years of age. For poor immigrants it was another tragedy in a long line of work disasters.

The International Ladies Garment Workers Union had organized in the sewing factories with mixed success. Public policy supported increased safety, better pay and standard hours. Life got marginally better over the next decades.

The great waves of immigration from the 1860s until the brutal Immigration Act of 1924 brought tens of thousands of workers for the sewing factories. Many had learned to sew at home. Some learned to do hand work or use the foot treadle or electric machines in the factories. They did hand work by the stove in the evening as young children and got paid by the piece, and later graduated to cutting from patterns or piecing or sewing at the machine. They learned from their grandmothers and mothers and sisters. Sewing for neighbors or family brought in a few dollars, made their homes more attractive, gave the children better clothing to wear. Sewing in the factories brought a wage, helped feed the family, taught them the necessity of organizing, working together for fair wages, safer working conditions and gave them the possibility of some economic independence.

Paola Corso’s poems illuminate the lives of women laborers. Here is another of her poems from her volume Once I Was Told the Air Was Not For Breathing that remembers several of the Triangle dead

Identified

Sophie Salemi

by the stitched knee of her stocking mama darned the day before

Ignatizia Bellotta

the heel of her shoe the cobbler repaired with a metal plate

Mary Levanthal

the gold cap Dr. Zaharia set on her wisdom tooth last week

Gussie Bierman

by the pendant watch she wrapped around her neck twice

Julia Rosen

the hair braids her daughter Esther fixed for her that morning

Rosie Grosso

the savings she wrapped in cheese cloth and hid in her left stocking

Kate Leone

by a blue skirt she wore to Randall’s Island hospital to visit her son

Jennie Levin

the baby’s sock found tucked in the heel of her shoe

Anna Cohen, Box No. 31

Celia Eisenberg, Box N. 56

Julia Aberstein, Box no. 32

On the lid of one coffin written with white chalk:

Becky Kessler, call for tomorrow

MOTHER JONES. Mary Harris “Mother” Jones, champion of child laborers, mill workers, coal miners and factory workers, worked as a school teacher and dressmakers before she began to organize for labor organizations. We know that she began her life in Cork, Ireland in the time of great hunger, lost her children and husband to Yellow Fever in Memphis, started her successful dressmaking business in Chicago only to lose it and all she owned in the great fire. The heritage of radicalism that she brought from Cork as well as her experiences with terrible loss informed her ideas. Her life among the rich of Chicago as she made beautiful clothes for wives and daughters gave her an intimate view of the contempt the rich held for working people.

Here is Mother Jones’ account of her dressmaking years from her Autobiography of Mother Jones:

“I returned to Chicago and went again into the dressmaking business with a partner. We were located on Washington Street near the lake. We worked for the aristocrats of Chicago, and I had ample opportunity to observe the luxury and extravagance of their lives. Often while sewing for the lords and barons who lived in magnificent houses on the Lake Shore Drive, I would look out of the plate glass windows and see the poor, shivering wretches, jobless and hungry, walking along the frozen lake front. The contrast of their condition with that of the tropical comfort of the people for whom I sewed was painful to me. My employers seemed neither to notice nor to care.”

Our Mothers and Grandmothers

Many immigrant families have passed down the stories of the lives as well as the beautiful handwork and clothing made by the sewing women. Following are two remembrances of immigrant women and their sewing lives, one from a daughter and the other from a granddaughter.